Few scandals in Texas history have caused as much political damage to so many as the one we call Sharpstown. Although it ignited fifty-three years ago, in January 1971, Sharpstown has had a lasting impact on this state. It ruined the careers of many individual politicians along with those non-politicians, like my dad, a lawyer who merely drafted some legislation. Most importantly, it weakened and, ultimately, shattered the Democratic party in Texas. Such was the intent of Republicans in the Nixon administration.

The seeds of the scandal were planted when the U.S. Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) received a tip that there were some stock trades involving the Governor of Texas, the Speaker of the House, and other officials at a brokerage firm in Dallas, Ling & Co. These were stocks in a company called National Banker’s Life Insurance (NBLI), which was owned by Houston banker Frank Sharp. Trading records showed that these purchased stocks were soon repurchased by the company at a higher price, producing profits for these politicians and associated individuals. It was soon discovered that Sharp had also lent money from his bank to these investors specifically for the purpose of making these stock purchases and manipulating the stock’s price. Some say that this was typical Frank Sharp, playing fast and loose with his bank’s money and currying favor with people he figured he could use to his advantage one day.

Even before Sharpstown, the Nixon administration had a couple of goals in Texas. As part of his Southern strategy, Nixon wanted to break the Democratic party’s political stranglehold in the state. Equally important, he wanted to kneecap any further rise to power by then Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes, whose political aspirations had been blessed by LBJ and who was becoming known in Democratic political circles nationwide. (Note 1) Having been the youngest Speaker of the House and Lieutenant Governor in Texas, he was well on his way to fulfilling the promise that the former president had recognized in him. Republican officials sought to keep that from happening. As mentioned in my last Sharpstown post, Nixon Attorney General John Mitchell and Chief of Staff H. R. “Bob” Haldeman would later apologize personally to Barnes for their roles in ending his political career.

So, with the SEC investigating the NBLI stock trades, Frank Sharp turned from being the owner of a bank, an insurance company, and various real estate developments, to a man facing numerous indictments for fraud and securities violations and possible prison time. He became putty in the hands of the Department of Justice, doing and saying whatever he could to stay out of jail, truth be damned. He entered into a plea agreement and fed the Feds lies. There were three main ones.

First, Sharp claimed that the purpose of the 1969 bank deposit legislation he championed and that was passed by the Legislature was for the purpose of allowing state banks to replace the FDIC with the state deposit insurance. If the FDIC were eliminated, banks like Sharp’s, for instance, would be allowed to escape FDIC regulations and federal oversight that Sharp considered bothersome and onerous.

Second, he claimed that he bribed state officials with NBLI stock, helping them purchase with his bank’s money to get the bank deposit legislation passed.

Finally, he swore that John Osorio — the lobbyist who was working for him — told him that he had bribed Ben Barnes with cash to help pass the legislation.

None of this was true, but it gave this weaponized Justice Department something to use for discrediting Democratic politicians, especially Barnes.

The Lie About Evading the FDIC

Regarding the first lie, the bill, as written, was clearly meant as insurance that would cover a customer’s deposits from $15,001 to $100,000 of deposits in state banks. As H.B. 73’s emergency clause, embodying the purpose of the bill, reads:

The fact that the depositors in banks in this state are limited in protection of insured deposits to the sum of $15,000 under federal law and the fact that such sum is totally inadequate in view of the inflationary pressure on the economy and the fact the citizens of this state should be provided with a mechanism for protection of deposits in excess of $15,000 create an emergency and an imperative public necessity …..”

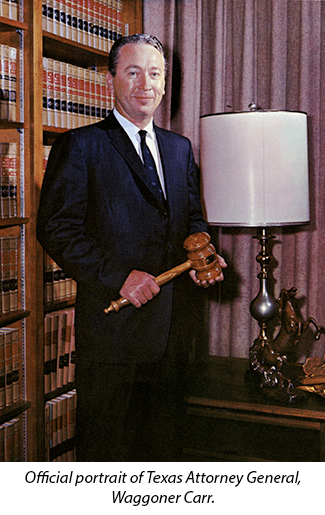

Former attorney general Waggoner Carr testified before the General House Investigating Committee that “[a]ll this gobbledygook about it being for the purpose of supplanting, or rather substituting, for FDIC was not in the picture at that time, nor so far as I’m concerned was intended.” (Note 2)

Even Sharp knew the true intent, writing to Speaker Mutscher in a letter dated February 19, 1969. In the letter, he explained that the bill is “predicated on the idea that the FDIC will have the first $15K and the State the 100K after that.” (Note 3)

Also, when the senate sponsor of the bills, Senator Charlie Wilson, testified before the House Investigating Committee he said that he understood the legislation as giving depositors added protection which wouldn’t cost them anything. “The idea that it was in lieu of FDIC insurance was never raised.” (Note 4)

The Lie About Quid Pro Quo Bribes

As to the second lie about bribery, here is the reality: These bills didn’t need bribes to pass. State deposit insurance wasn’t controversial and, in fact, it was mostly considered a good thing for state banks and small town banking in 1969.

Context helps. In the 1960’s state-chartered banks in Texas operated at a serious disadvantage compared to national banks located in the state. Think of Wells Fargo (national) versus First State Bank of Uvalde (state-chartered). The amount of deposits told the story. Customers in the 546 national banks in Texas deposited a total of $13,864,716, averaging $25,393.25 per bank. Customers of the 593 state-chartered banks deposited only $4,864,298 (averaging $8,202.86 per bank). (Note 5)

Home-grown state-chartered banks found it difficult to compete with national banks for several reasons. National banks centered their operations in metropolitan areas where customers were plentiful and more affluent than those in rural areas. That distinction gave national banks the perceived advantage of greater solvency, thus engendering trust, particularly from large depositors. Since the FDIC only insured deposits up to $15,000 for both state and national banks, trust in a bank’s size and overall solvency loomed large.

Another consideration justifying the state deposit insurance was that big depositors, such as pension funds and retirement funds, were hindered by the FDIC insurance maximum because they were limited to making deposits only to the extent they were insured. So, a $1.5 million investment in certificates of deposit, for example, would have to be distributed in 100 banks to obtain the $15,000 FDIC coverage.

With a state deposit insurance in place covering deposits up to $100,000, big investors could place $100,000 in each of 15 state banks, and the sponsors hoped that that amount of coverage would draw substantial out-of-state deposits to Texas banks. Thus, these banks would have additional funds they could loan for business establishment and expansion, especially helping banks and businesses in smaller towns. (Note 6)

“Hell, there didn’t need to be any bribery for those two bills to pass,” wrote Robert Spellings, recounting a conversation at the time of Sharpstown with District Attorney Bob Smith. He was Chief of Staff to Lieutenant Governor Barnes at the time. (Note 7)

And consider the individuals who took monies from Sharp to invest in NBLI stock: Governor Preston Smith, Speaker Gus Mutscher, Gus Mutscher, Sr. (the Speaker’s father), Dr. Elmer Baum (chairman of the State Democratic Executive Committee), State Representative Bill Heatly (Chairman of the Appropriations committee), State Rep. Tommy Shannon (state representative), Rush McGinty (aide to Speaker Mutscher), and F.D. Schulte, administrative aide to Speaker Mutscher. Of these eight individuals, four of them were not even officials who could vote on the passage of the bills or secure its passage in any way.

So what was going on? Two sources possibly explain it.

First, Spellings surprisingly admits that he and other legislative staffers often received what they thought were hot tips from brokers or businessmen attempting to curry favor with a particular politician. He recalled the following:

My old friend Rush McGinty would frequently tout a stock to me that he’d heard about, as I sometimes did for him… . If one of us got a tip that sounded good and one or both of us had or could acquire money to invest, we would buy as many shares as it seemed prudent to buy or that we could afford, not only for ourselves but often for our respective bosses, Barnes and Mutscher . . . (Note 8)

Second, in “The Texas Banker who Bought Politicians,” by James Reichley in Fortune magazine, Sharp was described as a poor farm boy from Crockett, Texas, who made it big in Houston, but was never quite accepted by the city establishment. Thus, he was always striving for acceptance and clout in Houston, and ultimately, in Austin.

A good example is how Sharp sought favor with the NASA astronauts, wanting to be associated with them and the burgeoning space program. Sharp tried to implement various programs to benefit the astronauts, like free housing and life insurance policies both of which NASA officials rejected. He successfully cozied up to James Lovell a friend of one of his sons-in-law. Sharp gave him 25,000 shares of NBLI stock, worth about $360,000. Lowell would say it was understood that at the proper time he would sell it and repay Sharp’s cost of the stock. Lovell later joined the NBLI board at a fee of $5,000 a month, which after a few months was reduced to $100, the monthly fee received by other board members. (Note 9)

When it came to the Sharpstown scandal and bribery, Reichley speculated that Sharp’s investment in the state officials was not a quid pro quo specifically for help with the banking bills:

What Sharp really must have had in mind, beyond passage of a single bill, was building up an indebtedness among the state’s politicians upon which he could again call at some future time. This was very much his style….He had, at least in his own mind, established a claim for future favor on the governor, the speaker of the house, the most powerful committee chairman in the house, the state chairman of the dominant party…. (Note 10)

I would also discount the quid pro quo bribery angle in regard to the banking legislation simply because common sense would dictate that anyone wanting to pass a bill through the legislature by bribing lawmakers wouldn’t just bribe one house of the legislature. They would certainly consider a senator or two. And yet none from that body received any of Sharp’s largesse. This leads us to the third lie.

The Lie About Barnes Taking a Cash Pay-Off

Frank Sharp’s third lie was telling the Feds that John Osorio paid the Lieutenant Governor, Ben Barnes a cash bribe to help get the bills passed in the Senate. Anyone who knew or knew of John Osorio would have picked out this particular lie. Osorio didn’t get his reputation as an effective lobbyist or maintain his law license by bribing people to pass bills. Plus, as Barnes’s chief of staff said, no one needed a bribe to pass this legislation.

The Justice Department would later try to bribe Osorio with a dismissal of the case against him if he would admit to Sharp’s claim that Osorio told him he had “taken care” of Barnes, and that “Ben is smarter than most of these other politicians, he only accepts cash.” After Sharp’s deposition, a reporter found Osorio the next day and showed him the page with those statements. Osorio read it and in the margin next to the statement writes, “Cheap trick…part of the SEC’s scrip[t]. Nothing like this ever took place with Ben,” and signs his name. Note 11.

Regarding the possibility that Barnes would accept a bribe, his ambition for higher political office makes him an unlikely candidate to risk his career for nothing more than a wad of cash. Barnes was a man with big plans for his future — ones that didn’t include going to prison for accepting bribes to secure the passage of a couple of bills involving bank deposits. Barnes paid little attention to these bill, as he was consumed with getting an expansion of the sales tax passed during that special session.

Barnes as a Target

Barnes knew that he had a target on his back and went out of his way to pay taxes and handle funds with great care. Every use of anyone’s airplane by Barnes for a personal trip, as well as a percentage of all the office phone bills were treated as income on which Barnes paid taxes. When the Nixon administration IRS audited Barnes, they could find no wrongdoing. Instead of finding criminality, they discovered that he was entitled to a refund of $3,800.

Lieutenant Governor Ben Barnes

Before it was all said and done, the Justice Department spent five million dollars trying to find dirt on Barnes to no avail. Anthony Farriss, former U.S. Attorney who extended the immunity deal to Sharp told a friend of Barnes years later, “Barnes was too clean, so extraordinary measures became necessary.” One such measure included granting Sharp immunity to say that “Barnes only takes cash.” (Note 12)

Although the House lost quite a few members in the “throw the rascals out” frenzy of the 1972 elections, no senator was particularly touched by the passage of the bank deposit bills. Charlie Wilson, for example, the Senate sponsor of the bills went on to serve in Congress in 1972. Even Babe Schwartz, senator from Galveston, served another 10 years, and he was a big fan of the legislation. In fact, he threatened to filibuster the bills unless the Senate approved an amendment that would allow private banks to participate in the deposit insurance program for state-chartered banks. His constituents never held it against him — certainly not his constituents at Galveston’s Moody Bank.

The only Sharpstown victim from the senate side of the Capitol was the Lieutenant Governor. This was partly because the name “Ben Barnes” was like “click-bait” on the internet today and the press was quick to throw his name into any story, or at least in the headlines, to pull in readership.

The Governor’s Veto

In regard to the Governor’s veto, some have suggested that had he signed the bills into law, he would have been indicted with Mutscher as another recipient of Sharp’s money and the NBLI stock deal. One has to ask whether he failed to understand that he had been bribed by Sharp, or whether there was simply never any quid pro quo associated with the investment scheme. Nevertheless, in his Veto proclamation, the Governor expressed great concern about the effects of state-chartered banks and saving and loan associations withdrawing from federal supervision (the FDIC).

Why was withdrawal a concern if this legislation was excess insurance that only kicked in once the FDIC had covered the first $15,000? The most probable answer is that Governor Smith was being lobbied by representatives of national banks that were feeding him fear tactics because they didn’t want the competition from state banks.

Another possible contributing factor is the Schwartz amendment allowing for the participation of private banks, such as Galveston’s Moody Bank. Private banks did not participate in the FDIC system. Once these banks were included, the intent of the legislation to provide coverage in excess of the FDIC was eviscerated. Would state banks then feel free to leave the FDIC system? A court might clear up any confusion by invalidating the amendment, but that would be an open question upon passage, contributing to the governor’s point about state banks leaving the system and and concern regarding the loss of federal oversight.

The 1972 Democratic Primary

But while the veto might have kept him from being indicted, Governor Smith would nevertheless be another politician to pay the price that Sharpstown exacted on Democratic office holders. Running for reelection n the 1972 Democratic primary, he won only 8% of the vote.

Additionally, Ben Barnes who had had nothing to do with Frank Sharp or his money was an unfortunate casualty in that primary. A third-place showing by a man who had been Texas’s top vote-getter at the age of 32 just a few years earlier demonstrated how effectively the feds and the press had smeared him with innuendo and mere suggestions of wrongdoing,

Additionally, another effort to smear him with Sharpstown was activated by Barnes’s primary opponent, House member Frances Farenthold. She published an ad with a picture of one of the bank deposit bills displaying his signature as Lt. Governor along with that of Speaker Mutscher. By using that signature, she meant to exploit the public impression that Barnes was one of the politicians who had been bribed by Frank Sharp.

What Farenthold purposely didn’t convey was that the lieutenant governor signs all bills that pass the Senate chamber before they are sent to the Governor’s Office for his approval or veto. That signature is required by the Texas Constitution, and, as a lawyer and a legislator, she knew that very well. (Note 13)

Barnes wanted to respond to the ad and explain the signature. He told me in a conversation last year that his campaign managers, George Christian and Julian Read, advised against it, telling him it would just confuse voters and further link him to the Sharpstown scandal. He reluctantly followed their advice. But there are many mornings, he said, when he still wakes up wondering whether an explanation of his signature would have made a difference. Could he possibly have won over doubting voters?

Would explaining that he had a constitutional duty to sign all Senate-passed bills have been enough? Would he have needed to further explain that there was nothing untoward about the bank deposit legislation? And the more he tried to explain, might it have had the effect his campaign managers feared?

Nixon’s administration wanted to eliminate Barnes from political contention and yet, they never found any thing unlawful or fraudulent to accuse him of — until they found Frank Sharp, a man willing to lie to save his own skin. The man Sharp fingered for paying off Barnes, John Osorio, could have avoided conviction and a prison term if he had agreed to corroborate Sharp’s lie. He refused to implicate an innocent man and became the only man to serve prison time in the Sharpstown scandal — for actions he took at Frank Sharp’s direction involving the NBLI pension fund, which I will explain in a future post.

I’m not sure a complete accounting can be done of the lives that Frank Sharp’s lies ravaged, and the collateral damage that ensued. But Nixon’s weaponized federal agencies used lies and innuendos to debilitate the Texas Democratic party, making Texas the state it is today — shamefully, a crimson red state with one of the most draconian abortion laws in the country, every gun toting provision possible, an indicted attorney general running amok, questioning election results, trying to dismantle environmental safety laws among many others. , . . shamefully a state that just helped elect another president who will weaponize federal agencies to pursue his political enemies and all those he considers threats.

Soon, I will tell you more about John Osorio, the man at the center of the Sharpstown scandal, whose name few in the public had heard of and even less remember. Stay tuned.

_______

Note 1. Barnes Ben. Barn Building, Barn Burning, Bright Sky Press, 2006, p. 186.

Note 2. General Investigating Committee Report to the House of Representatives, Deposit Insurance Investigation, January 1973, (GICR) p. 220.

Note 3. Carr, Waggoner. Not Guilty, Shoal Creek Publishers, 1977, p. 21.

Note 4. GICR, p. 89.

Note 5. Texas Almanac, 1968-1969.

Note 6. Senator Jack Strong, GICR, pp. 308-309.

Note 7. Beyond Politics, Aikers, Monte and Robert D. Spellings, 2024, p. 182.

Note 8. Aikers and Spellings, p. 52-53.

Note 9. “The Texas Banker who Bought Politicians,” by James Reichley in Fortune, December 1971, p. 99.

Note 10. Fortune, p. 143.

Note 11. Aikers and Spellings, p. 171; Barnes, p. 205.

Note 12. Aikers and Spellings, p. 198.

Note 13. Texas Constitution, Article 3, §38.