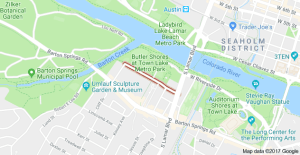

Yesterday, as I traveled down one of Austin’s neighborhood streets that does double duty as an east-west thoroughfare, I impulsively detoured from my route home. Some quirk of the mind summoned me to deviate a few blocks south to pass by a house my family occupied for a number of years after moving from Northeast Austin. From there, I decided to retrace the steps I took on my daily walk to Bryker Woods Elementary School where I attended the second semester of sixth grade, having moved in the middle of the school year.

The detour, in essence, was a trip down memory lane, or at least, an attempt to see what actual memories still remained along that lane. At the former residence, I noted that much was the same except for new windows partially installed and a proliferating landscape. Along the route to school, I vaguely recalled that I made my younger sister walk some distance behind me. Could I really have been so mean?

In vain, I strived to find familiar sights. I tried remembering what that sixth grader was thinking as she trudged along the street followed by her third-grade sister at a distance between “too close” and “not too far.” Was she dreading the day ahead thinking about the new friends she was slow to make and missing her old friends, her Girl Scout troop, and the school she had attended for over five years? Did she notice the irony that the name of the street she walked and the school she missed was the same? Harris. Was she wishing she didn’t wear glasses, had prettier hair, owned cooler clothes?

As I struggled mightily to reconnect with my younger self, I realized that this sudden nostalgia was an aspect of pandemic thinking. Many of us in isolation, no doubt, do more than take our temperatures and test our ability to hold our breaths for ten seconds. With so much time coupled with fear, I often find myself in these reflective moods, seeking keys to who I was and who I am now, pulling at existential threads, pondering my mortality, and wondering why we need bucket lists when the best thing in the world is just waking up healthy and hugging a loved one.

So my desire to reconnect continued as I surveyed the elementary school grounds that, of course, had appeared so much bigger in my memory. I noticed that portable buildings occupied the area of the kickball diamond where we used to play during recess. Strangely, I sensed my younger self the strongest on that missing playground. Waiting her turn to kick, she felt painfully self-conscious and awkward, hyper-aware of her failure to fit in with these girls.

In my mind’s eye, I could still see Ellen, one of my classmates, who was always the pitcher (for some reason) in the field’s center where she’d do a little dance as she sang, “There she was just a walkin’ down the street,” before she moved forward and let the ball unroll from her arm. I had a girl crush on this natural beauty – tall, thin, and blond with an animated personality. In short, she seemed everything I was not.

In comparison to Ellen’s coolness, my younger self was somewhat nerdy (had that word existed), overly serious, and inhibited. She no longer sensed the existence of that extroverted young girl who had lived in that northeast Austin neighborhood surrounded by friends, enjoying all kinds of play and activities. The result was that after a couple of years of relatively loneliness, she turned inward — surrendering that free-spirited self of her past. She developed coping skills — pretending that she was someone who was liked and fit in. Eventually, she began to believe in her act and was able to reanimate at least part of her authentic self.

But, unlike the children living through this pandemic, she wasn’t scarred by having to deal with a brand new world with life or death in the balance. She was not closeted away from others, from grandparents, the library, or the parks. She was not taught to fear contact with others – it would be many years until the “stranger danger” mentality needed to be taught.

I fear to think how plague-thinking will impact the children today, living in isolation with only parents and other siblings, feeling the world they knew dismantling piece by piece. Where does a third-grader, like my sweet grandson, find the psychological clutch to downshift into this smaller world without stalling or ruining the transmission altogether? Will these children be able to recover from this detour from their childhood, regain their footing and trust the world again?

We have to ask these questions because this is a crisis like no other in recent memory. It’s different because it’s so all-encompassing – not just a hurricane on the coast or even the World Trade Center attack on 9/11 in New York. “No, this affects all of us and all the things closest to us: our health and safety, our children and parents, our ability to move freely and sleep soundly, our ability to go to work and send our children to school,” says Charles Blow in his New York Times opinion column. And unfortunately, he notes, we have a president who can’t be trusted to show a modicum of competence, or the ability to at least partially quell our unease and foreboding. Trump’s handling of this episode guarantees that fear and panic generated by this pandemic will leave scars etched in the American psyche.

This makes sense to me. I know about scars, although mine are relatively small and personal, especially when compared to those chiseled by the Great Depression and the polio, tuberculosis, and other health epidemics. But, indeed, this experience and the alchemy of loss, loneliness, and fear will create wounds that will stain our days long after the pandemic ends. As we are whipsawed around on this leaderless train, all we can do is hold on … hold on to our sanity, keep up social distancing, hug our children close, and hold on to our belief in a light at the end of the tunnel. Safe travels, my friends.

Epilogue

The kickball pitcher, Ellen, and I reconnected years later as adults and she became one of my best friends. May she rest in peace. Ellen Roberta Bradley, June 5, 1953 — January 21, 2016.